MAY 2014

(sorry for the delay!)

CASE:

54-year-old male presents to the Emergency Department for evaluation of generalized weakness. He says that for the past 3 days he has had trouble speaking, trouble swallowing, dry mouth, and double vision. He says that his head feels “heavy” at night. He notes that symptoms started a few days after switching to a new dealer of his black tar heroin, which he injects into his thighs. He says his symptoms worsen throughout the day and with activity. This is his second ED visit for similar complaints – 3 days ago he presented to an outside ED for trouble swallowing and was told he needed endoscopy.

PMH: denies

PSH: ORIF R tibia

Meds: none

All: NKDA

SH: daily heroin use, social EtOH, + tobacco

VS: 98.7 163/92 80 18 100% RA

Remarkable exam findings:

HEENT: PERRL, discordant horizontal eye movements, ptosis noted b/l, dry mucous membranes

CV: RRR no murmurs

Neuro: slowly able to raise both eyebrows b/l though requires significant effort, speech clear though girlfriend at bedside notes it to be “different,” 4/5 strength on shoulder shrug, normal facial sensation, 5/5 strength b/l UE and LE, sensation intact b/l UE and LE, normal cerebellar exam, normal gait

Skin: warm, dry, no diaphoresis, skin popping sites visualized, scar tissue present without any evidence of induration or fluctuance

Labs:

CBC: WBC 5.7, Hgb/Hct 13.7/39.1, Platelets 236

Chem: 136/4.0/98/28/10/0.71/89

LFTs wnl

CXR wnl

APAP/Salicylate/EtOH undetedtable

Applicable case questions:

1. What is this patient’s differential diagnosis?

- Wound botulism

- Myasthenia gravis

- Eaton-Lambert syndrome

- Miller-Fisher variant of Guillain-Barre

- Paralytic shellfish poisoning

- Tick paralysis

- Lyme disease

- Endocarditis with septic emboli

2. What are the symptoms of wound botulism?

- Dry or sore throat

- +/- nausea and vomiting (more common with food-borne botulism)

- +/- fever

- Descending cranial nerve palsies

- Ptosis

- Diplopia

- Sluggishly reactive pupils

- Dysphagia

- Dysarthria

- Dysphonia

- Progressive symmetric descending paralysis

- Clear mentation

- No sensory loss

- Constipation and ileus from decreased motility

- Ultimately culminates in profound weakness involving respiratory muscles, can cause respiratory failure and death

- History of exposure:

- Usually skin popping, black tar heroin

- Wound may not be present – manifestations may occur 1-3 weeks after onset of skin infection

3. What are the different causes of botulism?

- Food-borne botulism: ingestion of preformed toxin in contaminated food

- GI symptoms followed by onset of neurologic symptoms usually delayed 12-36 hours

- Home canning – classic culprit

- Infant botulism: most commonly reported type

- Caused by ingestion of spores (not preformed toxin) in immature infant gut

- Risks: ingestion of corn syrup or honey

- Hypotonia, constipation, tachycardia, feeding difficulty, poor head control, diminished reflexes

- Wound botulism

- Classic culprit: black tar heroin

- Spores contaminate wound, germinate in the anaerobic environment, and produce toxin that is systemically absorbed

- Usually reported with skin popping – rare reports with open fractures, dental abscesses, lacerations, puncture wounds, GSW, sinusitis

- Adult intestinal colonization botulism: very rare – adult ingestion of spores (similar to infant botulism)

- Iatrogenic botulism: occurs following ingestion of botulinum toxin type A

- Botox (cosmetic purposes)

- Also used to treat spasticity, axillary hyperhidrosis, strabismus

- Symptoms occur 1-2 days after exposure

- Inhalational botulism: usually thought to be an act of bioterrorism, toxin is aerosolized, symptoms visible 1-3 days after exposure with longer onset times for low levels of intoxication

4. How is wound botulism diagnosed?

- Usually a clinical diagnosis made by symptoms, history of exposure, and attempts to rule out other causes of symptoms – need to intervene before confirmatory tests available

- Interestingly – many patients with botulism end up presenting to the Emergency Department or primary care doctor at least 3 times prior to the diagnosis being considered, due to nonspecific symptoms (i.e. dysphagia)

- Need to have a high index of suspicion

- Support for diagnosis can be found in EMG findings that differentiate from other causes, normal neuroimaging, laboratory work to rule out other causes

- Confirmatory testing done by determination of toxin in serum, stool, gastric aspirate, or a wound – usually via mouse bioassay (contaminated body fluid injected into mouse and observed for development of symptoms)

- Coordinated through the CDC

- Testing may be negative due to toxin levels below the level of detection

- Higher false negative rate in wound botulism than other causes

5. What is the management of wound botulism?

- Botulinum antitoxin

- Antibodies directed against toxins produced by C. botulinum

- Equine derived

- Binds circulating free toxin, prevents progression of illness

- Does not reverse established neurologic manifestations

- Most effective when given within 24 hours of onset of symptoms

- Obtained by contacting state or local health department or CDC

- ICU admission with close monitoring of respiratory parameters (NIF, Vital capacity)

- Respiratory failure can develop rapidly

- Often require prolonged intubation/tracheostomy due to paralysis of respiratory muscles

- BabyBIG (human derived antitoxin) used for infant botulism

- Antibiotics can be considered if a wound is present, along with wound debridement and irrigation

- Penicillin

- Avoid aminoglycosides – can exacerbate neuromuscular blockade

- Not usually recommended for other causes of botulism

CASE CLOSURE:

- Patient was admitted to the ICU and intubated within 6 hours of admission

- Antitoxin flown in and administered to patient as soon as possible – approximately 8 hours after initial ED presentation

- Neurology team followed closely and evaluated for other causes

- Prolonged ICU course requiring tracheostomy placement

TAKE-HOME PEARLS:

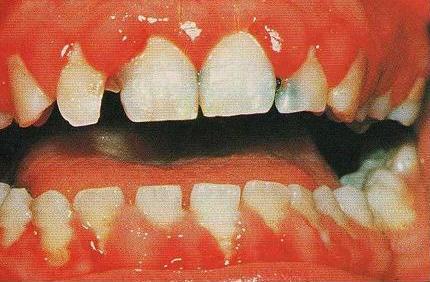

- Consider wound botulism in a patient with descending motor weakness or bulbar symptoms (diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia) + history of exposure (skin popping)

- See New England Journal Article from December 2010 - images in clinical medicine

- http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm1003352

- Need a high index of suspicion to make the diagnosis: frequently missed by Emergency Physicians

- Consider food-borne in patients involved in home canning, iatrogenic botulism in patients treated with Botox, infant botulism in infants with poor tone

- Admit to ICU and closely monitor respiratory parameters

- Antitoxin is obtained from the local health department or CDC: 404-639-2999

- Antitoxin should be administered as soon as the diagnosis is seriously considered, as it only prevents further paralysis – it does not reverse established paralysis once it occurs